Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

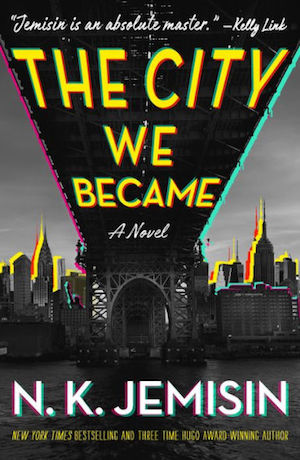

This week, we start on N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with the Prologue, first Interruption, and Chapter 1. The prologue was first published on Tor.com in September 2016, while the novel was published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead!

Note: The novel’s prologue is, almost verbatim, Jemisin’s short story “The City Born Great”. We summarized and discussed it in this blog post.

“…amid its triumph, the newborn city of New York shudders.”

“Interruption”

The still-nameless avatar of NYC collapses following his victory over the Enemy. The avatar of Sao Paulo crouches beside him, feeling the new-born city shudder. The NYC avatar vanishes, though the city hasn’t died. However, there’ve been “postpartum complications.”

Paulo makes an international call; someone answers with “Exactly what I was afraid of.” This is just like what happened in London. Still vulnerable, NYC hid its avatar away for safekeeping.

How many, Paulo asks. The equally cryptic answer: Just more. He must find one, who’ll track down the others. Though the battle was “decisive,” Paulo must watch his back. The city isn’t helpless, but it won’t help him. It knows its own, however. Paulo must make them work fast. It’s “never good to have a city stuck halfway like this.”

Where to start looking? Manhattan, Paulo’s advisor suggests, then clicks off.

Chapter One

The narrator, a young Black man, has forgotten his own name on arrival at Penn Station. He does remember he has an apartment waiting and that he’s about to start graduate school at –

He’s forgotten the name of his school. And from the chatter around him there’s just been a bridge accident, possibly a terrorist attack. Not the best time to move to NYC. No matter, he’s excited to be here. Colleagues and family think of his move as an abandonment, but – he can’t remember their names or faces.

In the station proper, he has a, what, psychotic break? Everything tilts, the floor heaves. A “titanic, many-voiced roar” overwhelms him. One voice is a “through line, a repeated motif,” screaming furiously that you don’t belong here, this city is mine, get out!

Narrator comes to attended by strangers: a Latino man, an Asian woman, and her daughter. Asked how he feels, he murmurs, “New. I feel new.” Two opposing ideas possess him: He’s alone in the city. He’s seen and cared for in the city.

As he assures the good samaritans that he doesn’t need 911, the world shifts from the crowded station to the same building empty and ruined. Then he’s back to reality. The woman and her daughter leave, but the man lingers. He asks for narrator’s name. Desperate, narrator christens himself Manny. The stranger, Douglas, offers money, food, shelter. Lots of “us” were new here once. Besides, Manny reminds Douglas of his son.

Somehow Manny knows Douglas’s son is dead. He takes the man’s card (Douglas Acevedo, Plumber) with thanks. Douglas leaves, and Manny looks up at the Arrivals/Departures board from which he took his new name, and with it an identity truer than any he’s claimed before.

That name is Manhattan.

After a restroom break in which he stares into a mirror and “meets himself for the first time,” Manny exits Penn Station. Reality shifts. Pain stabs his left flank, but there’s no visible wound. Around him are two simultaneous NYCs, the “normal” bustling one and an abandoned one in which some “unfathomable disaster” has occurred. Weirdly he likes this “bifurcated beauty.” He must do something, or both visions will die.

Manny senses he needs to go east, to FDR Drive. He’s drawn to a taxi stand and his intended “ride”: an antique checkered cab normally rented solely for weddings and films. Nevertheless, Manny convinces the young white female driver to take him to FDR Drive in exchange for $200. In NYC, money’s more than currency–it’s magic, a talisman.

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

The driver, Madison, drives with expert recklessness. Stopped at a light, they both see anemone-like tendrils growing out of a car’s wheel-wells. No one else seems to notice. Manny tells Madison that the two of them will destroy the tendril-maker if he can get to FDR Drive.

On FDR, Manny notices rescue activity on the East River, responding to that bridge disaster. The wrongness he’s seeking is closer. They see more cars tendril-infected and then the infection’s probable source: a thirty-foot-high fountain of “anemoneic” impossibility exploding from the left lane. Though blind to the monster, drivers are creating a jam by edging into other lanes.

Manny uses Madison’s emergency gear to cordon off the left lane. From the city, even from the delay-enraged drivers, he draws strength. He hears the monstrous tendrils stutter and groan, smells a brine scent that belongs to “crushing ocean depths.” From an Indian woman in a convertible, he obtains an umbrella as an improbable weapon. Then he mounts the cab’s hood, and Madison charges the “fountain.”

Manny senses the tendrils are deadly poisonous; instead of wielding the umbrella like a lance, he shelters under it. Energy surges in him, around him, forming a sphere around the cab. Ecstatic, he realizes that he’s no interloper to the city, that it needs newcomers as well as natives.

The cab tears through the monster, setting off a cascade of eldritch decomposition. On the other side, Manny clings to the hood while Madison brakes to avoid jammed cars. They watch the tendril-fountain burn to nothingness and the protective sphere explode into a concentric wave that wipes out all the vehicle-infections.

Manny realizes the battle was won through the energy of the city, centered in himself. His pain, which was the city’s, fades. He knows who he is: Manhattan. And the city wordlessly replies: Welcome to New York.

This Week’s Metrics

What’s Cyclopean: “…he can hear the air hissing as if the tendrils are somehow hurting the molecules of nitrogen and oxygen they touch” is honestly one of the best “not compatible with our physics” lines I’ve encountered.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Manny is deeply concerned that passersby will get him committed to a mental hospital, but also suspects he’s having some sort of mental breakdown. This comes up often enough to seem a clear choice: deciding that you’ve gone crazy lets you avoid reality-defying problems, but keeps you from solving them. Madness in this case takes a very specific toll, and “please have exact change” takes on a whole new meaning: change is exactly what’s needed

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“The City Born Great” ends in triumph–and with the promise of New York, thriving and grown into itself, helping the next city to emerge. The City We Became starts with nearly the same text—but with the triumph collapsed into something more complicated. And with that promise cut off. Held back until later, I hope, but no longer certain.

I loved the triumph… but in practice, triumph transmuting to complexity is sure a thing that happens. What does it take to turn revolution into thriving sustainability? When you’ve won enough to change the world, how do you make the new world work—despite the continued scheming of whatever you’ve overthrown, and despite having to be livable for people who may have been pretty comfortable with the old world?

These are slightly different questions than “What about that tentacle fountain growing in the middle of the highway?” But I have a suspicion that they aren’t too far afield from where all this is going. On this read, our original narrator’s “That shit ain’t no part of me, chico” rejection of yoga-loving white girls jumps out. Is that rejection, that reflexive pushing away of the people who push him, part of why New York gets stuck? Is that why New York needs more than one avatar, and why Manny loses his previous name and goals and any biases that may have gone along with them?

This is why I travel with a printout of my planned itinerary.

Alternatively, maybe Manny loses his previous name and goals because they mattered to him. The first, unnamed, narrator already loved New York more than any other attachments, even to his selfhood. Paolo is named for his city, so perhaps every avatar gets there eventually.

As in the original story, Jemisin’s own love for New York, in all its gritty specificity, shines through. The people who stop what they’re doing to help Manny are quintessential New Yorkers. I’m now failing to track down the source for an archetypal comparison between Californians and New Yorkers seeing someone with a flat tire: “Aw, man, that looks like you’re having a bad day” versus irritable and swear-ful help jacking up the car. It may be somewhere in this entertaining Twitter thread. New York is driving into an urban fantasy fight in a prop cab with a guy you just met, and New York is ratty vape shops, and New York is impatience with anything that slows you down–whether it’s a tourist standing still on the sidewalk or the remains of Cthulhu’s broken-off tentacles.

Manny’s love for New York embraces this contrast in full. His dual vision of New-York-as-it-is, crowded and loud, and New York abandoned to shadows, reminds me of Max Gladstone’s recent Last Exit, where it’s all too easy to slip from our best of all possible worlds to post-apocalyptic horror. But Manny sees beauty in both version of the city. “Gorgeous and terrifying. Weird New York.” Even the anemone-like filaments leftover from Other Narrator’s race across the FDR have their beauty, despite being toxic to the newborn city and also in the way of traffic.

Seems like someone who can embrace everyone in Manhattan, even the yoga girls.

One other line in these chapters struck me particularly, an off-note amidst excellence that wouldn’t have felt so off when the book came out in early 2020 (March 24, 2020, to be specific, which explains why it’s been sitting in my TBR pile for two years): “This is what he needs to defeat the tendrils. These total strangers are his allies. Their anger, their need for a return to normalcy, rises from them like heat waves.” Two and a half years later, I can only say that I wish I could see that desire for normalcy as a constructive force, rather than a vulnerability that lets parasites take hold.

Give the adversary an advertising budget and a few Twitter bots, and anemones tentacles growing over your car and into your body will simply become something we need to accept for the sake of the economy.

Anne’s Commentary

In my note above, I remarked that the Prologue to The City We Became was almost word for word Jemisin’s earlier short story, “The City Born Great.” As far as I could tell, skimming the two versions, she changed two things. The brief coda to “Born Great,” set fifty years after its narrator becomes the avatar of New York City, is gone. Given that the novel opens right after the principal event of the story, this makes sense. The other change is to the close of “Born Great’s” main section. In the stand-alone short, the victorious narrator proclaims: “I am [NYC’s] worthy avatar, and together? We will never be afraid again.” In the Prologue version, he begins with a shout and ends in a stutter:

“I am its worthy avatar, and together? We will

never be

afr–

oh shit

something’s wrong.”

The “stuttering” configuration of the words graphically shows the narrator’s breakdown from triumph to confusion and panic. As we’ll learn in the next section, “Interruption,” the narrator is about to disappear. He’s one moment in Paulo’s supporting hands, the next he’s vanished into the air’s suddenly acrid humidity. S’okay, though, he’s not dead because the city’s not dead. He’s just exited the scene for a while so that the city can protect him. And so that a new narrator can be introduced center-stage.

We still haven’t learned how the first NYC avatar will rename himself. In my comments to the story blog, I figured he’d call himself “York.” Readers had other ideas. Ebie thought of him, fittingly enough, as “Basquiat.” Kirth Girthsome suggested the appropriately accented “Yawk.” Scifantasy came up with “Nick,” for NYC, get it?

As it turns out, we don’t have a name for our new narrator either for several pages into Chapter One. There’s an excellent reason for that. See, he’s forgotten his name himself, apparently shedding it like a too-loosely pocketed candy wrapper while hurrying through Penn Station. It’s believable that he doesn’t notice he’s forgotten his name for a while–I don’t think of myself by my name because to me I’m ME, no other designation necessary. Shouldn’t he be more immediately worried not to remember the grad school he’ll be attending, and the names and faces of his friends and family? No, their names and faces don’t matter anymore, only that they didn’t approve of him moving to New York, and that they were wrong, because New York is his future. Erase what was superficial about his past life. It’s his core self that New York recognizes as its own.

Specifically, the part of NYC known as Manhattan, or for avatarial use, Manny. Huh, so a living city can have subavatars! That, I assume, is what Paulo means when he asks his advisor “how many,” given that the greater metropolitan area of New York is freaking huge. The advisor, I assume, is the Hong (for Hong Kong) whom Paulo mentions in “Born Great” as the one who first opened his eyes to the truth about city sentience. Hong’s all, don’t spaz out. Paulo only has to find one subavatar–that one will be able to track down the rest. Start with Manhattan, why not? Most tourists do.

Hence Manny who, forget his birth name, was always meant to come to New York, was always at core a part of the city, so that the Penn Station Samaritans don’t believe that Manny is a newcomer and the bike agent says Manny “ain’t no tourist. Look at him.” Nor can it be a coincidence that Manny arrives just when Manhattan needs a borough-avatar to pinch-hit for NYC Itself. Nor that he draws to himself (or has sent to him) others who are city-to-the-core, like Douglas the plumber and Madison the boutique-cabbie. Are these others sub-sub-avatars? Madison, at least, can see the remnants or precursors of the Enemy as Manny does.

Do we see a Fellowship of the Big Apple forming here? Because every Enemy worthy of its capital-E surely will require more than one borough to successfully oppose it. And, in conclusion, wouldn’t giant invisible sea-anemone monsters explain a lot about highway conditions in our great cities?

The Federal Government should form a special commission to look into it. Also, full Warp Speed ahead on the development of vaccines to protect our cars from tendril infection! Because most insurances don’t cover it, let me just caution you.

Next week, Kelly Link warns us about babysitters and haunted houses in “The Specialist’s Hat.” You can find it in The Weird.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out July 26th. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.